Standing at the intersection of a sidewalk and a sandy trail, my pulse begins to beat in my limbs, as if I’ve spent too long confined to a self that’s smaller than my imagination. I stretch my legs, roll my neck, raise my arms and prepare for flight, even if it’s only the one-foot-in-front-of-the-other human kind.

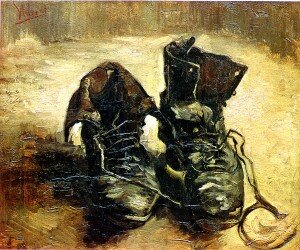

Restless and twitching, I think of Vincent Van Gogh’s famously long walks. The artist once traveled 100 miles by foot in three days just to visit his sister. His urgent sense of adventure is one of the reasons I feel drawn to Van Gogh. I once drove 1557 miles in record breaking time, from Key West to the Midwest, simply because my mind was too full and I needed a long, reflective drive followed by heart-to-heart contact to pour off the excess.

I suspect that Van Gogh, who struggled with his overfull spirit, as well as finding a place in the world, thought less about painting during his walks than he did about his purpose. I imagine that as sweat poured from Van Gogh’s sunburned skin, and his feet blistered in over-worn boots, he called out to both God and nature for the kind of relief he’d never known except in small doses. Van Gogh loved the complexity of God and the simplicity of nature. In his lifetime he strived diligently to be the obedient son of one and the conscientious guardian of the other, but neither took away his human need for belonging.

I suspect that Van Gogh, who struggled with his overfull spirit, as well as finding a place in the world, thought less about painting during his walks than he did about his purpose. I imagine that as sweat poured from Van Gogh’s sunburned skin, and his feet blistered in over-worn boots, he called out to both God and nature for the kind of relief he’d never known except in small doses. Van Gogh loved the complexity of God and the simplicity of nature. In his lifetime he strived diligently to be the obedient son of one and the conscientious guardian of the other, but neither took away his human need for belonging.

Toothless, chronically poor, emotionally pained, and yet steadfastly idealistic, Van Gogh often begged for the company of other artists and willing women—going so far as to pay for the privilege when he had coins to spare—yet at the end of his life he was considered a loner. I don’t believe loneliness was the intent of Van Gogh’s unquestionably heaven-bent spirit, but it may have been the result.

Van Gogh straddled two seemingly incompatible spheres of reason: the one he created from the matter of his own soul and experience; and the rigid, worldly one that seemed to run almost mechanically, with little regard for human nature. As he struggled with the demands and disparities of the material world—as he assessed the unconsciousness of the rules and systems he was supposed to abide by—Van Gogh turned questioning, stubborn, and argumentative. According to biographers, Van Gogh’s “negative” attitude and somber thoughts made others uncomfortable. Further, his poverty made him suspect and his unrefined habits, (particularly when it came to his later escape into alcohol), made him undesirable.

During his brief career as a clergyman, Van Gogh was thought to relate too personally to his lowly, hunchbacked charges—he was reprimanded for being too Christ-like in his Christianity—for laboring alongside the overlabored and wanting to share their conditions. (A pastor, Van Gogh was told, should hold himself above the fray and present an image lesser others could aspire to rather than one that shares their misery).

As an artist, at least in his lifetime, Van Gogh was an abject failure. His art was seen as crude and unlearned. It took years and probably thousands of paintings before he sold a single work of art and only then because of the unwavering support and salesmanship of his art dealer brother, Theo.

“I wish they would only take me as I am,” Van Gogh once said. Of course, outside of his brother, no one did, at least never for long enough to matter. However, Van Gogh’s posthumous and often fabled legacy of starry, starry nights and weathered faces lined in pain shouldn’t overshadow his less celebrated effort—the one shared today by countless others, who scramble up and down the wild banks of life, largely alone, sometimes out of choice, sometimes by way of rejection, but always hopeful and always ready to find that one true thing, person, or place that feels like belonging.

This internal/external struggle shared by many artists and idealists, who often find their hopes for humanity pitted against the grueling machinations of humankind, is as lonely as it is spiritual. It’s a call for communion between self and all-other, reality and longing, soul and reason. It’s a quiet contest to keep what we instinctually know is (or could be) true ahead of the pabulum churned out by the unconscious everyday machine. And it’s always a restless battle, whether we’re walking 100 miles, gazing at a starlit sky in unfamiliar territory, or tossing and turning alone in our beds.

The want to belong and be accepted by something more than one’s self would seem to be antithetical to the need for solitude, but I believe they stem from the same root. The God inside of us—the far-reacher of love, ideals, imagination and other high-hope arts—needs time alone to create the framework into which all else is meant to fall. This framework is never quite complete. It’s a living thing that often needs restructuring or expansion. Still, as it grows around our human experience, the nature inside of us wishes nothing more than to share all that it contains.

Breathe with me

feel with me

love with me

Let me reach inside of you

as you have reached into me

I will give you everything

if you give me just one thing—

all of yourself for all of me.

I remember the roadsides I’ve walked late at night, wondering at the alchemy of my own transmuted heart. When the rain is bitter, my skin toughens. When the press of time rages at me and I despair of ever finding my way or a sense of place, I remind myself that I was once stronger than a riptide that tried to drown me. And when all is well and good—when all the truths I know can lay bare and unashamed on my lap after a day of exhaustive exploration—when friends have blessed me with loyalty and care and I am in a place that feels safe and warm—the desperate pleas of the past transmute into calmness. There’s peace in knowing that I spoke out loud: That uncertain, sometimes frightened, I held my heart open to possibilities. And I’ve strived not to linger in the loss of my pride on those occasions when the most vulnerable of my pleas met with silence or reprobation. Instead, I asked myself what I could live without, and I learned to live without those things. I shifted my dreams, rearranged my necessities, and learned to walk my own road, appealing to the highest of Gods and the lowliest of deserts for whatever remained absent in the human world.

The unread writer

the unloved lover

the childless mother

the broken whole

transmutes into—

the unafraid truth

the winged ideals

the resilient soul

the love of innocence—

a different kind of whole.

The art of transmutation—whether a gift from the heavens or a thing learned from nature—creates a spectrum of possibilities, some which arrive easily and others that seem to require a long, painful journey.

On days like today, restlessness courses through my marrow and it feels like something is calling out to me, but I’m not quite sure what it is other than a change of some sort. Perhaps it’s a turn of thought or a sun-sparked inspiration, but it could just as easily be a purpose I need to find or a doubt I need to overcome.

“If you hear a voice within you say ‘you cannot paint,’ then by all means paint, and that voice will be silenced.” – Van Gogh

And if you need to walk into the starry night until Van Gogh is beside you and your weathered face becomes unlined with pain, then do. Walk until your heart is its own conscientious guardian again, uncorrupted by desperation and the senselessness of the world. Walk until the only question that remains is ‘what will I create next’?

Dear Vincent,

I think you might like this catalpa tree in bloom,

with its delicate pink flowers and wood-like pods.

Then, too, there are the scrubby pines and sagebrush

which, when the sun sets just right,

go from dull green to a peculiar shade of silver.

I’m alright. Torn in places, whole in others.

I could probably use a new pair of shoes & a new far-off dream

to keep me grounded while I fly into the next book.

Love,

Jane

Paperback now available! Kindle Edition Available Now on Amazon. Other e-versions at Smashwords.Other outlets coming soon!

Paperback now available! Kindle Edition Available Now on Amazon. Other e-versions at Smashwords.Other outlets coming soon!

Add to Google

Add to Google My Yahoo

My Yahoo

Comments on this entry are closed.