I went fishing once. I liked sitting quietly on a boat in the middle of a serene lake. I liked the near-silence and the feel of the sun on my skin. I liked just sitting there, staring into the sky or water. What I didn’t like was everything else. The bait, the waiting, the wide-open eyes of the fish being reeled in. Even halfway out of the water, they looked like frightened ghosts. I was sure that even those who escaped suffocation were haunted by the experience of being pierced by a hook. After the first death, I removed my pole from the water and asked my companion to throw her next catch back. One fish was surely enough for dinner, especially since I wouldn’t be eating.

I didn’t feel the same way when I went abalone diving. There were no eyes to contend with, only hard beautiful shells to collect and bloodless white meat to pound into tenderness before it was sliced, battered and fried. In the salty ocean air, with wood smoke from a camp fire burning my eyes, I ate my fill along with my children and friends. Afterward, I watched my green-eyed daughter and brown-eyed son wander off in search of the perfect sticks to roast marshmallows.

On that day, just like nearly every day before and since, I wondered who I was. Most often, the thought was fleeting. I’d see someone who looked like me and wonder if we shared roots. Sometimes, I’d ask strangers what nationality they were and then, if they were game for conversation, cagily get them to guess at my own. I’d flip through the pages of a magazine looking for someone who shared my features. On occasion, the thoughts lingered. Who was I to have this son who looked just like me and a daughter who looked so opposite? My children were a mirror that reflected a past haunted by one unanswered question: who am I really?

My mother, MJ, would never tell me and, in fact, seemed to delight in holding the power of her secret. I was a ghost fish she reeled in and decided to keep as a resented pet of some sort. I cannot number the times I wish she’d have thrown me back or given me away. Instead, she dined on her secret while I squirmed and flailed about looking for some sense of identity, of belonging, of love.

It is hard for me to speak with adopted children who resent having been adopted, even when they were raised with love and care. Many of them seem to imagine that had their mothers kept them, their lives would be complete. They believe I am lucky because at least I knew my birth mother. Never mind that she was cold and unwelcoming, or that I spent every day of my childhood wondering what I did to deserve her wrath — at least I knew what she looked like and who she was. I do not feel lucky for having that knowledge. I wish that MJ had the strength and the integrity to understand her limitations. I wish that she’d been able to set aside her great pride to say, “I made a mistake by having this affair and neither my husband or I want this child, so I will let her go to someone who wants a child and who won’t punish her for my sins.” MJ didn’t have that kind of strength, though. Her pride, not her desire, made her keep me. It would have been too humiliating to explain to the mistake of her third pregnancy to her older daughters, her family, or her neighbors. It was easier to pass me off as her husband’s child — to tell strangers who inquired about my coloring that there were dark-eyed Gypsies on her side of the family.

On Facebook, a young Korean adoptee rails against the picket fences and dance lessons of her white-parent youth. She bemoans being “bought” as a baby in an international adoption and shipped to an American suburb, to diligent parents who gave her warmth, security and love without a biological imperative. This is an outrage to her. She has read The Primal Wound and believes that being given up by her birth mother has forever damaged her. She believes that, no matter who her birth mother was, or how her life might have turned out — no matter how poor, dire, or even resented she might have been — she would have been happier, more whole, more like herself had her birth mother kept her. One half of me understands. She is a ghost fish, too. Wide-eyed, she was pulled up from her natural element and taken to another pool, by people who do not look like her and who probably could not answer her most pressing questions, even if they wanted to.

The other half of me is jealous. Envious to the point of frustration, really. I want to tell her that it is better to be rejected early, with finality, rather than rejected day by day, every day, piece by piece, until the fact of your mother did not want you, cannot love you, will never love you is not only the seed of infancy, but all the branches of childhood and beyond. There is no warmth in that cold water of resentment. No guidance and no solace. No hands, not even unfamiliar ones, to hold onto. No dance lessons, no one to cheer you on, or pick you up when you fall. There is only you, with a gaping hole in your heart and a torn-up psyche. You become your own parent, eventually. You learn to nurture and encourage yourself, but it’s not the same. Somewhere, always, you’re waiting for that mother-voice to say, Good job. I’m proud of you. You are a worthy human being. The voice does not come, so you pretend it; you create it for yourself, maybe through other women, other relationships.

(There comes a time when a lover’s hands are more than precious . . . when they become extensions of everything you ever wanted and never had. Sacred, those hands. Exalted, that shelter of arms that cradle you so many years past the age of a cradle. Your lover will be bemused by your fascination with her hands. By how humble and reverent you feel, laying skin to skin, your plain, dark hand on the altar of her angelic white hip. She will never know how much it means to you that she lets you lay there — that she has invited you to lay there — that, for even a short while, she gives herself freely to you and finds you worthy of this privilege . She will not understand why the tears rise so easily, or exactly why you love her so much, or how very deeply that love goes. She will not understand many things and you will only be able to explain so much without sounding like a madwoman or scaring her off. You are like a church with open doors, where I might wander in and hear a sermon of love and forgiveness. Here, our communion wine on the nightstand. Here, our window, closed to the unholy city. Here, we will gather love and grace instead of coins, so that even a pauper might feel rich. You don’t say that, though, you never say that. You smile with her. You tell her yes, I know it’s silly how much I love holding your hand in the car or stroking your hair until you fall asleep. I know I sound like an idiot when I try to tell you why having my hand on your hip feels sacred to me or, worse, when I imagine out loud a pretend future of morning walks and Sunday dinners. I just love you, that’s all, go with it.

None of it matters in the end. You get thrown back or throw yourself back for any number of ungodly reasons, not the least of which are those slight religious differences that determine levels of pride, acceptance, shame, compromise, risk, mutuality and love).

The religion of the ghost fish holds that Heaven is a person who loves and wants you, and a place you feel accepted. The opposite of heaven is the hell of rejection.

I did not want my son to be a ghost fish. My envy of adoptees is why I wanted to surrender him for adoption. I wanted him to have all that I could not give him and all that I suspected I would never be able to provide. I was beyond poor and knew that it would not be temporary. I knew how hard I’d have to work and how little time I would have. I knew he would suffer for my sins through endless hours of daycare, financial crises, and severe shortages. I did not want him to suffer. My most profound regret in life is that I allowed my mother and her husband to intimidate me into keeping Mac and then later sharing custody. My son, like me, does not feel grateful to have at least known his mother. I do not blame him for this at all. I gave him so little to be grateful for. I raised him in chaos, in poverty. He ping-ponged back and forth. I did not have the resources to fulfill his needs. My love, although strong, fell abysmally short. He told me once that he forgave me and maybe he meant it at the time, but it took me 27 years to unwrap the heavy chains of guilt from around my heart and forgive myself.

My son had a father who never saw him, never paid child support and never cared, but I’ve found in relaying the story of my son’s life to strangers that there’s no anger or judgment against the man who simply left. No one, not even once, has ever expressed any surprise or outrage that a father could do such a thing. When it comes to children, it is the mothers who are scorned for their imperfect choices — for not being able to pick up the pieces, or right all the wrongs — for their poverty, chronic instability and desperate decisions. But you were his mother. You should have done better. You should have tried harder. You shouldn’t have let him live with your parents. How could you? I would never give one of my children up, no matter how bad things got.

Many woman I know, and certainly the women in my son’s life, think they could have given more, worked harder, and been wiser under the same circumstances. None of us will ever know if they are right, and this many years later, it no longer matters. The past will not change with judgment and the future will not be bettered by recrimination and guilt. I do not tell stories like this for personal catharsis, but in the hopes that other young women might learn from my mistakes — to let them know what they might find if they follow either my course or my mother’s. Becoming a parent before you’re fully grown up, before you’re stable and ready, can be painful and full of lifelong consequences. Keeping a child you do not want or cannot care for is a guarantee of damage.

I am a ghost fish daughter and the mother of ghost fish son. I would wish it to be different, but it’s not. My son and I move in different elements, but I am convinced there is a place of love and acceptance for both of us, still, in this life.

It was my 50th birthday the other day. As a present to myself, I ordered a DNA genealogy test. It will not tell me who my father was, or why my mother was so determined to keep him a secret. It will not erase the past or substantially change my future. It might tell me where my brown eyes come from, though. I might be able to stop saying “I don’t know” when people ask what my nationality is, and maybe I’ll even stop wondering myself. It will take a laboratory 6-8 weeks to pry my mother’s secret from my blood.

It is not everything, but at the same time it is so much. This is the half of me that understands the ache of adoptees. This is the half of me that can’t stand fishing, but that still needs to fish.

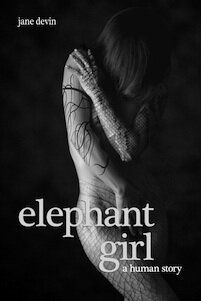

Paperback and Kindle Editions Available Now on Amazon.

Paperback and Kindle Editions Available Now on Amazon.

Add to Google

Add to Google My Yahoo

My Yahoo Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook

Comments on this entry are closed.