Ishan Patel’s mother hated him from the day he was born prematurely in January 2011. Diagnosed with postpartum depression, Neha Patel, a pharmacist, was given medication to deal with her condition. However, like many depressed people, Patel seemed unable to commit to regularly taking an antidepressant. News reports don’t mention whether she was being seen by a psychiatrist or was in any other type of therapy. What they do say is that Patel, age 32 and the mother of a four year-old girl, quit her job at CVS on February 12, 2012. Four days later, on February 16, she murdered her one year-old son while her husband, Rasesh, was at work and her daughter was in daycare. The official cause of death was drowning, but the autopsy also revealed blunt force trauma to the head.

Ishan Patel’s mother hated him from the day he was born prematurely in January 2011. Diagnosed with postpartum depression, Neha Patel, a pharmacist, was given medication to deal with her condition. However, like many depressed people, Patel seemed unable to commit to regularly taking an antidepressant. News reports don’t mention whether she was being seen by a psychiatrist or was in any other type of therapy. What they do say is that Patel, age 32 and the mother of a four year-old girl, quit her job at CVS on February 12, 2012. Four days later, on February 16, she murdered her one year-old son while her husband, Rasesh, was at work and her daughter was in daycare. The official cause of death was drowning, but the autopsy also revealed blunt force trauma to the head.

Patel told detectives that earlier in the day the child was crawling toward her. To discourage him, Patel struck the boy twice in the head and then put him in his crib for a nap. When he awoke, she filled a garden tub with water, put her son in and then left the room, closing the door behind her. According to Patel’s statement, the boy was submerged and unconscious 10 minutes later and although she knew CPR, she chose to wrap Ishan up in a blanket and go for a very long drive. She knew the baby was dead, she’d later say, because he was cold and blue. She considered suicide, but eventually decided to return home around 2:00 in the morning.

Patel placed the baby in the crib again and then confronted her husband, who demanded to know where she had been. When she told him that she’d drowned their child, Rasesh didn’t immediately call 911; he began frantically calling relatives. This angered Naha Patel, who screamed that she wasn’t going to prison and that she would kill herself first. She left the house and drove to the Tampa airport, where police discovered her around 1:00 p.m. the next afternoon.

Internet message boards are bursting with the usual comments, calling for Neha Patel’s blood or at least the rest of her life in prison. There are those who insist that no matter how mentally disturbed she was, Patel — an educated woman — should have the wherewithal to take her medication, call for help, stop herself, or even choose to end the misery of her own life instead of her child’s. There are those who believe the father should be charged, since he knew his wife was ill and he still left her alone with their son, although he took the daughter to daycare.

Internet message boards are bursting with the usual comments, calling for Neha Patel’s blood or at least the rest of her life in prison. There are those who insist that no matter how mentally disturbed she was, Patel — an educated woman — should have the wherewithal to take her medication, call for help, stop herself, or even choose to end the misery of her own life instead of her child’s. There are those who believe the father should be charged, since he knew his wife was ill and he still left her alone with their son, although he took the daughter to daycare.

The story of Andrea Yates is brought up as a point of contention. Detractors claim the mother “got away with” murder after an appeals court eventually found her not guilty of the deaths of her five children in 2001 by reason of insanity. However, Yates is still in a mental hospital where there’s no definitive end to her sentence.

What bothers me about the Patel case (and others like it) is the overriding public belief that mental illness is, at least in part, voluntary, and that those who suffer from severe depression and even psychosis, are capable of making the same sound judgments or having the same rational thoughts as those who don’t, or those who suffer more mild symptoms. A significant number of people will bring up their own stories of postpartum depression (or those of their sister, cousin or friend) as if to say, “See? We knew better. We didn’t kill our kids. PPD/psychosis just isn’t that bad. It’s no excuse for murder.” These kinds of comparative tales might make people feel better about themselves, but they’re essentially useless. PPD/psychosis is not a disease of morals; it is caused by a severe chemical imbalance. Making it a matter of oneupmanship in the arena of willpower is about as useful as saying, “Hey, I drove when I was drunk once and didn’t kill anybody, so you shouldn’t have either.” The level of imbalance in depressive and psychotic conditions differs. Living arrangements, support, treatment and other factors all play a part.

Popularized by courtroom dramas, almost everyone knows that the legal definition of insanity is knowing the difference between right and wrong at the time of the criminal act — but that belief is misleading in part, not only because “insanity” isn’t a psychological diagnosis and is purely a legal term — but because there’s another, less often mentioned factor in determining criminal culpability, and that is the ability to control impulses.

“Not guilty by reason of insanity” is rarely a successful defense, not only because the burden of proof is set incredibly high, but also because attorneys know that the emotional impulse factor will not outweigh the question of being able to intellectually differentiate between right and wrong. The obvious problem with this is that mentally ill people are not operating in a rational space. They may intellectually know right from wrong as surely as they know the difference between red and blue, yet they may not have the ability to defuse the emotional time bomb that has taken over their minds.

The legal definition of insanity leaves thousands of mentally ill people in prison, largely untreated. I won’t argue that society isn’t better off with men like Jared Loughner locked up for life, but I’ll always wonder if tragedies like the one he perpetrated would have been prevented if we lived in a country that took mental illness more seriously.

As for Neha Patel, if it is proven that postpartum psychosis is at the root of her actions — if outside of this very treatable and usually temporary illness she has no other criminal tendencies — I don’t believe justice would be served by locking her up for life. While she probably shouldn’t have any more children, it’s highly unlikely that after treatment she would represent a danger to society.

Ishan Patel was killed by his mother, but there’s plenty of blame to go around. Neha Patel, who had been formally diagnosed with PPD, should have been better treated and monitored. She should not have been left alone with either of her children. The many red flags in this woman’s life should have been paid closer attention to, but they were not. It’s unlikely that Neha’s husband thought she would go so far as to kill their son, but did anyone along the way take the time to explain the potential dangers of Neha’s illness to him?

Ishan Patel’s face tells a story . . . but is anyone listening?

There are too many Ishan’s in our world. Too many children born into volatile circumstances to parents whom, for any number of reasons, do not or cannot care for them. Miraculously, some of these children survive — often without outside help — only to be faced with a culture that is so heavily invested in bootstraps and bromides that it demands survivors become “accountable” for their own damages, and develop the knowledge, means, and willpower to overcome deeply emotional consequences. Any failure to do so results in accusations of “making excuses” . . . and the cycle continues.

Look at Ishan. Do you think that had his mother not killed him, but merely continued to hate him, that he would have grown up “normal”? Do you think that an infant who is routinely slapped, neglected and despised grows up with the same abilities, thoughts and choices as one who was not? Do you imagine that at some point in Ishan’s development, he would come into the knowledge and skills to rewire himself, by himself, into a happy and “normal” young man? If you do, you’re certainly not alone.

Our American “do it yourself” culture routinely diminishes the longterm affects of child abuse, just as it diminishes the realities and consequences of mental illness. It doesn’t matter how much scientific research exists to disprove the “bootstrap” theory — it is easier to blame the mentally ill for their poor characters. It is easier, later, to blame their victims for not being stronger, smarter, or surviving the right way.

The only thing that will ever break this cycle is a cultural revolution in which shallow, knee-jerk outrage and blame is replaced with an appreciation for logic, science, and objective truths. Feeling sorry for deceased children like Ishan, or railing in hatred against mothers like Neha, does absolutely nothing for them or for future victims of mental illness or childhood abuse. Pity does not alleviate death, much less pain, and hatred does not prevent tragedy.

If we truly care about the state of a cyclical culture in which tragedies like the Patel’s keep being repeated, we need to stop making our own excuses: “It’s not our problem — other people should know better — it’s not up to us to pay for someone else’s mistakes,” because clearly it is our problem, other people don’t always know better, and one way or another society does pay. We pay for our emotional arrogance and contrived lack of understanding every time there is a preventable tragedy. Autopsies, trials, prison stays, foster care, social services, state attorneys . . . the list of costs is millions of dollars and years-long. Yet instead of demanding a rational and comprehensive re-haul of mental health programs and policies, we cry out for blood and punishment.

Mahatma Gandhi once said,”There is a higher court than courts of justice and that is the court of conscience. It supersedes all other courts.” When it comes to the treatment of mental illness, the collective conscience of America is profoundly lacking. It needs to evolve past its primitive bootstrap theories and convenient bromides and understand that ill is ill and that mental illness, especially the kind that comes with psychosis, is not a voluntary condition or a question of moral character.

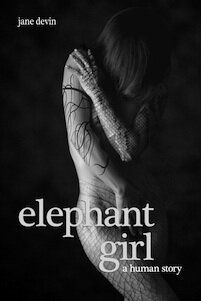

Paperback and Kindle Editions Available Now on Amazon.

Paperback and Kindle Editions Available Now on Amazon.

Add to Google

Add to Google My Yahoo

My Yahoo Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook

Comments on this entry are closed.