Several years ago, a well-connected woman in the literary world sent me an email after a friend of hers shared something I’d written. She told me she thought my story was insightful and my voice was unique. I felt honored and we began to exchange emails in which we shared thoughts about our work and our personal lives. Her letters to me were filled with ideas about inclusiveness, diversity and equality. Then I heard, through another source, that she was editing an anthology of stories that seemed like a good fit for me. I asked her if I could submit a piece. My new friend, who had highly praised my writing, skirted the issue. I was taken aback by her reluctance and kept digging until I finally got the truth. In less gracious terms than she put it, she would be embarrassed to include one of my stories in her book. I had no real credentials. The writers she planned on choosing were either established or on their way up, while I was not.

The truth hurt, but at least it let me know who I was in her eyes. I was always going to be the backroom girl to her, at least until someone else took a chance and published my work. She wasn’t going to be the first, though. It was just too risky. (Later, she tried to placate my hurt feelings by making my “outsider” status a cause for celebration. “It’s really where you’re at that makes your work so moving,” she told me. “You don’t want to give up that powerful element up for the sake of being like everyone else.” In other words, I should have felt privileged by her rejection instead of hurt).

At about that time, there was a new show on television called “Starting Over”, which featured women trying to improve their lives with the help of life coaches. I’m usually not much of a television watcher, but the show’s premise fell right in line with what I felt I needed in my life — a complete life makeover. I didn’t want to be the backroom girl forever. I didn’t want my past or my work to be viewed as a source of embarrassment to others. How could I reframe my past in order to create a brighter future? I was hoping “Starting Over” might provide some ideas. I followed the program into its second season, intrigued by some of the women and their stories. That was the last time I saw “life coach” Iyanla Vanzant until I watched an episode of Oprah’s Lifeclass last Friday night.

(As an aside, I was excited when I heard that Oprah Winfrey was going to create her own network. I imagined that OWN might fill the gaping space between slanted news shows (FOX) and ignorance as entertainment (Jersey Shore). I have no idea what’s planned for the future on OWN — I’ve only seen a small portion of “The Rosie Show” — but I wish it every success. The criticism I’m about to share isn’t meant to criticize Oprah or the network, just the contents of this one show I did watch. Besides, I have mad respect for the kind and generous Sheri Salata and want her to succeed).

Back to Lifeclass. I didn’t remember Vanzant as being quite so far out there with her spiritual beliefs in her “Starting Over” days so I was stunned when, during Oprah’s program, she authoritatively advanced such cosmic gems as “children choose their own parents” and insisted that even abusive, neglectful parents must be honored.

Vanzant’s opinions are hers and she’s certainly entitled to them, but what was disturbing to me was that there was no challenge to even the wildest, most far-fetched of her opinions. At a certain point I thought, ‘Oh, Oprah’s going to argue with that’, but she didn’t. It felt like Oprah, who’s supposed to be the head teacher of Lifeclass, let the substitute run the course without question. I was surprised by that, but then perhaps the show served its purpose after all. Hearing Vanzant impart her beliefs as if they were gospel, the only truth and way, stoked several ‘aha’ moments for me . . . which are really less about Vanzant herself and more about spiritual guruism in general and my own, long road to healing.

Aha Moment #1 - Intellect is not the enemy of spirituality. Applying intelligence to a spiritual concept should not weaken it but — if it’s a reasonable concept — make it stronger.

You can, for example, choose to believe as Vanzant does — with absolutely no proof whatsoever — that through billions of people, chance meetings, sperm and eggs, you chose your parents. You can believe that whatever experience you had with them, including abuse, was some sort of preordained spiritual lesson you had to learn, but let’s not couch our language. Essentially, this philosophy holds even the youngest victim responsible for whatever befalls them in life. If they chose it, then they had a hand in their abuse (or whatever else they may have suffered). If they chose to be tortured, beaten, raped, physically disabled, or emotionally scarred, then it was essentially for their own good — to teach them some lesson they needed to learn.

Even putting aside the (very rational) question of why human beings might need lessons in sexual, physical or emotional abuse, this “spiritual concept” is not only devoid of reason, but also lacks anything approaching compassion or empathy, even for oneself.

It’s not much of a philosophical jump to believe that if a pre-born soul had the power to choose their parents, then they also made choices about other major events in their lives. Therefore, the murder victim might have pre-chosen a violent end in order to become a better person in the afterlife. The murderer might have chosen to kill to teach himself a spiritual lesson. The child born to warmth and love chose her path, as did the child born to cold and neglect. If everything is pre-destined, there’s no such thing as random luck or chance, or even perverse human will. Everything that happens was meant to happen, even when it appears to be less godly than rooted in a corrupt human system. Kim Kardashian receives $17M in payment for a marriage, Troy Davis is executed, and Snooki becomes a published author — all for the benefit of their (and perhaps our) spiritual growth.

Under this umbrella of nonsensical thought, where God / The Universe / A Higher Power is ultimately responsible for all things, human beings become nothing more than pawns in a rough and never-ending game of enlightenment. As pawns, tied to the heavenly will and dictates of a universe beyond their reach, the belief would appear to be that people are essentially powerless to become more like the Most-High they claim to have faith in — peaceful, wise and loving — without endlessly repeating and perpetuating illogical, unwise and unloving experiences. And apparently, although God is perfect and infallible, he created billions of slow learners.

Perhaps you believe that and feel comforted by the thought that there’s a Bigger Plan out there. One that you can’t possibly know the true meaning of because you are, after all, only human. Now that you’re flesh and blood, the great power of choice you had as a pre-born being (when you got to choose your parents and therefore a significant part of your destiny) has been transformed into the mortal choice of feelings. You don’t remember choosing abuse (or whatever tragic thing happened) but you must have, your beliefs say, because it happened. Now, your spiritual lesson here on Earth is to struggle through a morass of emotional hell and ultimately choose the feelings that will make you feel like it was all part of a big cosmic plan meant for your enlightenment.

This line of spiritual belief is so preposterous — it makes such a game out of human suffering and consequences — that I have a hard time contemplating how any thinking being would consider it possible, much less desirable or healing on any level.

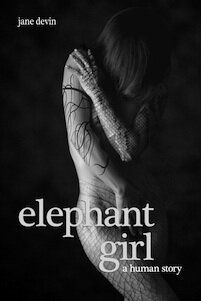

When I wrote Elephant Girl, I talked about straw sanctuaries — the beliefs we hold, often mystical in nature, that make us feel better about a situation, at least temporarily. A belief like “there are no accidents” gives seeming reason to everything under the sun, from betrayal and rejection to violence and death. The tangible and physical truth, though, is that accidents do happen. Often and every single day. A parent turns their head for just a few seconds . . . a skier crashes into a tree . . . someone leaves their wallet in the restroom. We can and do learn lessons from accidents, but most often they are wholly human. We learn to be more conscious and aware of our surroundings. We learn regret and remorse. We learn to grieve and heal. We learn humanity through our own accidents, tragedies and mistakes as well as those of other people. This is affirming in itself. We don’t need to believe that God (whom we imagine should love us) — decided to drown our child, paralyze our friend, or make us lose our rent money in order to teach us a lesson.

We aren’t expressing much love for our own God or higher power when we choose to make them the bearer of all that’s bad, irrational and painful in the world. What we’re really doing is turning away from the concept of God as a loving, accepting, beautiful entity and remaking him (she or it) into an emotional abuser. We’re either creating God in our own, human image or calling up a punishing, Old Testament God who would lay a child upon a rock to be killed as an act of faith or wipe out a nation for the sins of a few.

And if this is what you believe — that God, the Universe or some higher power puts people through hell to test their faith or teach them a lesson — then that’s your right, but please, let’s not call it enlightenment. It’s a belief as old as the Bible itself and it is steeped in fear. Fear that we or others won’t do the right thing without a punishing parent in the wings — fear that our hearts are not as clean or pure as they could be — fear that we can’t or won’t evolve on our own.

It’s possible to be a spiritual being who believes in a God/higher power/Universe that is above wanting to hurt you, or anyone else in the world. It’s possible to have faith in a most-high spirituality that does not seek to perpetuate, redeem, or justify the bad acts of human beings.

You can believe logically — because there’s plenty of evidence to prove it — that human beings are at the center of most social/world/personal problems . . . Or you can believe that a perfect, loving and powerful God views us as children that need to suffer for our own betterment.

The difference between the two beliefs is that we can do so much more with the first one. If we know, for instance, the kind of human experiences that lead others down a path of violence, we can work toward prevention. If we know that children born in poverty have a higher incidence of permanent brain damage (and we do), then we might be motivated to help change their circumstances out of compassion. If, however, even on some small level, we hold the belief that people choose their fate — that even the worst circumstances are somehow God’s will — than we’re also going to question our own power (and rightness) in interfering. When we make God the scapegoat for all tragic human events and suffering we not only lessen the concept of God, but our own power to empathize, feel compassion, and affect the world around us.

I choose to hold my higher power above myself. I do believe there’s something almighty, supremely intelligent, and beautifully soulful in the world. I feel it in the very best part of myself and other people. I feel it when I look out upon a star-filled summer sky or see the grace in which an animal moves in its natural habitat. I feel it in moments of perfect, quiet communion and spontaneous bursts of pure joy. I just don’t believe that such a powerful entity as God — such a perfect and transcendent being — wrestles in the mud of everyday humanity. I think it’s more likely that it’s been left to us, in all of our imperfect but knowing humanness (and we do know so much better than we let on), to take care of and solve our own failings. I believe this is our task. We are charged, as individuals, to learn as much as we can; to give the world the best we’ve got; to help others fulfill their potential; and to love with the full and considerable power of our own, human hearts.

I believe this is the part of God, the power and strength of God, that exists within us most tangibly and powerfully.

Aha Moment #2 – We perpetrate spiritual violence when we cannibalize our intellect and ability to reason.

During Lifeclass, Iyanla Vanzant said that picking up a cell phone while speaking in person with someone else was an act of “spiritual violence”. It was, she said, dismissive of another human being’s spirit. I’d agree that it’s rude and inconsiderate. However, I’d also suggest that Vanzant isn’t aware of her own contradictions. Could there possibly be a more spiritually violent belief than one that holds that children, particularly those who are abused or neglected, chose their own parents? That actually promotes that concept as an advanced (I think she referred to it as ‘level 403’) belief? What could possibly be more dismissive of another human being than saying that they chose, in their pre-born life, to be beaten, choked, starved, raped, or left to die in a cage?

Applying “an intellectual construct to a spiritual concept” is something Vanzant called someone out for during the show. On the contrary, I would say that failure to apply our intelligence to spiritual beliefs is what causes, in the larger scheme of things, catastrophes like Jonestown and Waco. In an individual realm, it leads people down spiritual rabbit holes which may appear enlightening at first, but that really end up nowhere and serving no one except the rabbit in any real, tangible manner.

Whether you believe in God or a higher power — or you don’t — you can’t reasonably deny that the mind is a large part of who we are. We have the ability to reason . . . for a reason. The intellect is not anti-spiritual. If it were, there’d be no Mahatma Gandhi, Confucious, Buddha, or even the Bible. Our souls are not mindless or devoid of rationality. To divide the soul from our minds is to make enemies of ourselves, which is a form of spiritual violence with far greater consequences than answering a cell phone while at lunch with a friend.

Aha Moment #3 – There are many roads that lead to healing. Some are short and don’t last in the long-term, but provide needed temporary relief. Others are long, winding roads that eventually take you where you need to be. However, when someone tells you that you must take road A or B in order to really heal, they are stating their opinion, not a fact.

The fact is that there is no one perfect, correct and one-size-fits-all way to heal. Those who promote such a way are only stating their opinion, based upon their own thoughts, experience and, in Vanzant’s case, their religious beliefs. If your belief system is similar to that of the person giving advice, you might find what they say helpful. If it is not, taking their advice may cause more pain and confusion, and may even be damaging.

One of the most common (and in my opinion) harmful fallacies in abuse recovery is that of forgiveness. Therapists and spiritual gurus go so far as to redefine the actual meaning of the word in order to cajole their clients and adherents into accepting the false premise that forgiveness is necessary to heal. I’ve written about this subject extensively before, but it bears repeating: You don’t have to forgive someone who hurt you in order to heal your pain. Forgiveness may not be merited, you may not feel compelled to give it, but you can still heal. I would encourage anyone who believes otherwise to read this very articulate piece by renowned psychologist and true child abuse expert Alice Miller. Just one line from Miller speaks to the experience of thousands of survivors who, like me, found it far more healing to reject than to forgive:

“It was my experience that it was precisely the opposite of forgiveness – namely, rebellion against mistreatment suffered, the recognition and condemnation of my parents’ misleading opinions and actions, and the articulation of my own needs – that ultimately freed me from the past.”

Neither Miller’s spirit or mine — or the spirits of thousands of others — were damned by our decision to reject the concept of forgiving of our abusers. Instead, we forgave ourselves for those horrible times we questioned whether we did something to deserve being beaten, choked, or raped.

We rationally looked at the behavior and actions of those who abused us and said no, forgiving you is not a genuine want or need of mine. At that moment and forever after we unchained our spirits from our abusers. We put our own desires — our own ethics, feelings and thoughts — above those who harmed us. We removed ourselves from the cycle of abuse by rejecting our abusers and their actions wholly and without regret. Once we were out of the cycle, we didn’t have to hate or fear our abusers — we also didn’t have to try to love, understand or accept them. We could move on with our own lives, untie our morality from theirs, disconnect our hearts from theirs, and thus take them out of the equation of our healing. Free from the socially enforced and religious “good child” mandate of forgiveness, many survivors, myself included, found an inner peace and calmness that they couldn’t access before.

That’s not to suggest that forgiveness is unhealthy or wrong, only that if it’s in a person’s heart to forgive and they find it helps them heal, then they’ll do it and they won’t need to be talked into it or convinced that it’s the right thing to do. They’ll know. Just as others know when it’s not right or wouldn’t be healing for them.

In short, there are no hard and fast rules to healing. There’s no one way, because we’re all individuals. You may choose to forgive a parent who abused you because it makes you feel better, but it does not mean that someone else is wrong, immoral, or less spiritually evolved than you for choosing not to do the same. Our experiences as individuals are uniquely our own, as are our spirits.

Aha Moment #4 – Spiritual gurus (and so many others) deny judgment at the same time they’re pronouncing their beliefs to be superior.

Anyone with any amount of life experience judges others. A five year-old entering a kindergarten classroom judges the teacher to be nice or mean and judges which of her peers will make the best playmates. If you’re out walking late at night and cross the street because you see someone who looks dangerous coming your way, you’re judging. We judge our surroundings and other people every day. Judgment is built into our DNA and it’s not a shameful thing unless it’s used consistently poorly or to harm or denigrate others.

Many spiritual gurus deny that they judge while at the same time making broad, sweeping judgments. Vanzant did this during Oprah’s Lifeclass, when she insisted that a woman who was abandoned by her father must honor him because, after all, he lent his body to God in order to create her. To not honor him, no matter what kind of person he was or what he’d done, was to dishonor herself. Vanzant used her religious beliefs to shame a woman who, probably after years of consideration and painful experience, decided her father wasn’t worthy of honor. Vanzant then briefly tried to reframe the definition of honor to make it a more palatable concept. (I’ve noticed that many spiritual gurus seem to develop an “anything it takes to get someone to go along” attitude when it comes to promoting their personal beliefs. Forgiveness, then, doesn’t have to mean to absolve or pardon, and honor doesn’t have to mean to hold in great respect or high esteem if adherents balk too much at those definitions. Words can take on different or situational meanings, as long as the language fits with the overall program being promoted).

My life has given me several opportunities to interact with spiritual gurus. My sense of realism has often butted up against mystical concepts like “write yourself a check for a million dollars, believe it, and it will happen”. However, the only time I’ve ever felt personally affected by someone else’s beliefs is when they were used to belittle, invalidate, or dismiss my experiences. Most recently, this happened when a “life and wellness coach” told me that God hadn’t financially blessed me because I wasn’t through learning all the lessons of poverty. No matter how hard I worked or what I did, she said, God would keep me poor until I was “ready to receive” blessings. Talk about a judgment. She not only invalidated my work, but also presumed to speak for God and soothsay my future. She used her religious belief system to irrationally speak to and justify a life experience that was not her own.

Over the years, spiritual gurus have told cancer victims that they caused their own disease by repressing their emotions. They’ve suggested that those who died didn’t pray hard enough or have a positive enough attitude, while those who survived did. They’ve suggested that the rich are rich and the poor are poor because of Karma or destiny, and that God has a wise, unknowable hand in all tragic events, including genocide and starvation.

This is what happens when we separate our intellect from our spirituality: We insist on a certain type of perpetually struggling ignorance that has us chasing after cosmic reasons from God while the obvious reasons are often right in front of our faces. We turn humanity — God’s own creation — into a blind and dumb species that can’t grasp simple concepts like accidents, randomness or cause and effect, but that presumes it’s wise enough to know God’s intentions. We turn God into a petty, punishing buffoon who not only preordains or oversees the details of billions of lives, but who keeps reinventing the same human predicaments for his own, humanly unfathomable reasons.

I believe most of us truly know better than this. We’re wiser and more knowing than the spiritual gurus would have us believe.

This is part two of a three part series. Part one is here. Part three is here.

Paperback and Kindle Editions Available Now on Amazon.

Paperback and Kindle Editions Available Now on Amazon.

Add to Google

Add to Google My Yahoo

My Yahoo Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook

Comments on this entry are closed.