I got the news that he died in an Oregon hospital yesterday after a short struggle with cancer and COPD. According to my daughter, the nurses enjoyed him while he was lucid. He flirted, in his own awkward way. He was 83.

My daughter cried on the phone. She felt guilty for not being there in his final moments. “He was proud,” I told her. “He probably would not have wanted your last memory of him to be as a frail man in a hospital bed.”

“I loved him,” she said. I told her I know she did and that her grandpa knew it, too. In my mind, though, I thought of the Norman Edwards she didn’t know. My daughter had only gotten to know Norman well in his 70’s, and while he wasn’t a changed man he was much weaker and probably much more lonely. She enjoyed his brash and crusty conversation—she found him funny. They bonded over the military: he retired from the Navy after 27 years; she was a flight medic in the Air Force.

He wasn’t really my father, but I didn’t get solid confirmation of that until I was well into my 30’s. Lying was a paramount requirement of being part of the Edwards’ family, especially for me. I was not to ask why I looked so different than my two older sisters, or why the sparse amount of parental care in the house was never directed at me. “You’re bad,” my mother told me. “Get out of my way, nigger lips,” Norman said.

When I was little, somewhere between a toddler and kindergarten, I believed I was from Mars. The people from Mars weren’t green and little, they were tan and strong. I used to meet them near a ditch by our house. We’d make mud pie babies and then set them free in the brackish water. I didn’t know the story of Moses then, but I was sure the mud pie babies would be saved and find good homes. I wanted to find a good home, too. I wanted nothing more than to escape.

“She’s breathing too hard again,” my sister Dianne complained in our Fallon, Nevada living room. “I can’t hear the TV.”

“Stop breathing,” my mother yelled from the kitchen. And I tried to quiet the rumble in my lungs, but shallow breathing only made it worse and I began gasping for breath.

“God damn you,” my mother screamed as she grabbed my arm. “Why do you always have to cause trouble?” She dragged me to my room, threw me on the bed, and pummeled me with her fists.

This was to be my job in the family—to be the whipping girl—but I didn’t know it then. I only knew that I was despised. Nigger lips, liver lips, ingrate, troublemaker, piece of shit, a monster, a pig.

One of my first memories of Norman was when my mother got us all up early one morning to go meet him at an airport. I was about three, so my sisters must have been about six and eight. We wore white dresses and hats and had memorized a song to sing to him. He walked down the terminal, an imposing figure in a black uniform. Like good girls, we stood in line and waited to be greeted. He reached down to pat the backs of my two older sisters and ignored me. Tears welled up in my eyes. This was my dad? Why didn’t he see me? I swallowed my tears and sang the song. As we were walking to the car, I tried to hold his hand. He brushed my hand away and put it in his pocket.

I remember when my baby sister was brought home. I was so excited because I thought she’d be mine, the same way that my two older sisters belonged to each other. I was determined to be the best big sister ever. I would rock her and sing to her and teach her about the Martians. As the car pulled up to the house, I stood outside eagerly. Norman exited first, with the baby in his arms. I stood on my tiptoes and begged to see her. “Keep your filthy hands away from her,” Norman ordered. Eventually I did see my sister—I was surprised to see that she had a shock of black hair and almond eyes like me. As she grew, her skin was even darker than mine.

(As an adult, Deborah did manage to figure out who her real father was. He was, I believe, an American Samoan who was once friends with Norman. By the time she was born, it appears that my parents had reconciled to the fact that they both had affairs, my mother’s resulting in two births—one a twisted surprise and the other just a simple fact. Neither believed in divorce, so they stayed miserably married but kept separate bedrooms after Deborah was born. Perhaps because of this understanding between them, Deborah was accepted into the Edwards fold. That acceptance never did extend to me. I was the original shame—the one my mother failed to pass off as her husband’s.)

Norman did his best to ignore me but sometimes he couldn’t. Sometimes my mother’s hands would tire of beating me and she’d tell him he had to take over. He did so with methodical efficiency. Sometimes I made the mistake of walking in front of his precious television set and blocking his view. He’d jump out of his recliner, red faced and angry, and slap me to the ground.

At nine, I was a quarter short of being able to go to a Saturday matinee with my friend Carol and her family. I begged Norman, and he told me I’d have to earn it by washing his car. He kept coming out to inspect it and finding flaws. The matinee came and went. I kept cleaning the car, inside and out. I cleaned the vents with a toothbrush and shined the wheels. He found lint on the windows left behind by a paper towel. He found bugs I had failed to get out of the grill. Finally, eight hours after I began, at 6:00 at night, he begrudgingly handed me a quarter.

Whenever I needed money after that I would beg the neighbors for odd jobs. I began babysitting early and often, and discovered that other people’s houses were nothing like mine: That most children didn’t leave the house as soon as they could in the mornings and return as late as possible at night. Most kids liked being home, or at least close to home. I avoided mine whenever I could, learning to innertube down the Truckee river to downtown Reno. I learned how to take buses, and to walk or bike ride for miles. Being away from home was the only time I could imagine being some other girl, belonging to other people, belonging even to a brightly lit city, a field of sagebrush, or a swift green body of water.

When I broke a basement window at 10 and my parents sent me off to be molested by strangers for the summer, I could not tell them. I came home a changed girl, but no one seemed to notice. We had company that winter and my bed was offered to them. I was to sleep in Norman’s bed. When he entered the room and took off his robe, I began to shake and cry. “Are you….are you going to….make love to me?” I asked. They were the only words I knew for what happened to me that weren’t cuss words.

“What the hell are you?” Norman boomed. “Some kind of pervert? Get the hell out of my room.” I went to the couch, but I didn’t sleep. I laid awake all night worried that I had let my secret out and would be punished. The subject was never brought up again.

When I was 14, I spent all day in the bathroom getting ready for my first date. When the doorbell rang and I was getting ready to leave, Norman told me I looked like a slut. I met Gilbert at the door with wet eyes I blamed on allergies.

I have one good memory of Norman. When I was 16, he inexplicably sold me his 1970 Datsun 2000 for $200. It was a sporty looking convertible, British racing green with black leather interior. Sometimes it ran and sometimes it didn’t. I spent whole paychecks from my jobs making repairs that never seemed to stick, but when it ran I loved that car. I loved putting it in 5th gear and cruising up and down I-80, pretending I was one of those girls from Reno High School who ran track and who were invited to proms, and not the girl with the GED who worked 40 hours a week so she could afford her own clothes and pay rent to her mother.

I have one good memory of Norman. When I was 16, he inexplicably sold me his 1970 Datsun 2000 for $200. It was a sporty looking convertible, British racing green with black leather interior. Sometimes it ran and sometimes it didn’t. I spent whole paychecks from my jobs making repairs that never seemed to stick, but when it ran I loved that car. I loved putting it in 5th gear and cruising up and down I-80, pretending I was one of those girls from Reno High School who ran track and who were invited to proms, and not the girl with the GED who worked 40 hours a week so she could afford her own clothes and pay rent to her mother.

I left home five months after getting the car. I took a bus, found work in the Silicon Valley and rented a run down studio apartment. I lived there a little over a year and then returned to Nevada.

I visited my parents when my maternal grandmother, who had Alzheimers, came to live with them. It was a horrifying scene. My mother wanted her dead—she called it an act of mercy—and kept giving her too much or not enough of the several medications she took. There was a lock on the bedroom door so Nana could not get out. When she was out, Norman was violent with her. He pushed her when she moved too slow and yelled at her when she was confused. One night she struggled to get her 4’10” body out of depth of couch cushions. He was trying to watch television, and her movements aggravated him so much that he got up and threw her across the room. My mother did nothing—she just sat in her matching recliner. I comforted my Nana as best I could. I gave her a bath and put her to bed. In the morning I called Social Services. Nana was moved to an extended care facility shortly after that.

No one tried to kill my mother when she was dying of bone cancer. No one threw Norman across the room when he got old. That’s the way it should be, even if they were short on mercy themselves, but I wonder if on their deathbeds they ever asked for forgiveness. I wonder if they ever gave any thought at all to the lies they told, the abuses they meted out, and the damages they caused. My guess is that they did not. My guess is that like many people they rewrote their own versions of history and cast themselves as people who “did the best they could”. That was one of my mother’s favorite lines, but it was also a lie. I don’t recall her ever stopping in the middle of an outburst or beating to consider what she was doing. And when she knew she was dying, she didn’t offer up any apologies or needed truths. She promised me once that she would tell me who my father was before she died. When the time came to tell me, she said no—it didn’t matter. She held the one truth I ever needed from her hostage. She used it as a weapon, and managed to get one more shot in before she died in 1996.

It had been about two decades since I’d spoken with Norman. He went to his death, from what I’ve heard, fairly easily and without pain. He left no final words.

When I met up with one of my older sisters last year she said, “What does biology matter? He wasn’t a very good father to any of us, but at least we had one.” She does not have the same memories that I do, but she wasn’t the one that was despised and beaten. On that topic all she had to say was “well, you really pushed their buttons.”

My daughter has different memories, too. She did not know Norman as I knew him—when he still had strength and took out his bitter resentments with words and belts. She knew him as old, hard-nosed, and crusty in a way that made her giggle. I’m happy for that. I’m happy that my daughter was beautiful and worthy in his eyes, even if I was not.

But I can’t cry for him or about him. Those tears were spent years ago.

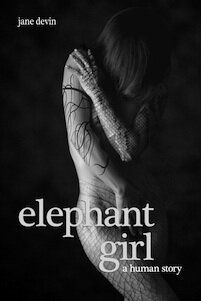

Paperback and Kindle Editions Available Now on Amazon.

Paperback and Kindle Editions Available Now on Amazon.

Add to Google

Add to Google My Yahoo

My Yahoo Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook

Comments on this entry are closed.