100 years or so from now, there will be another Les Miserables, and another audience that does not recognize its own social wrinkles in the distant folds of history. They will rail against injustices and cheer for another Jean Valjean — perhaps this one dogged by a 21st century three-strikes law that mindlessly, soullessly imprisons men for life. They will feel contempt for a petty character like Madame Victurnien — “the guardian and door-keeper” of everyone else’s virtue except her own — who stalked Fantine’s life in the hopes of doing her harm.

Madame Victurnien sometimes saw her passing, from her window, and noticed the distress of “that creature” who, “thanks to her,” had been “put back in her proper place,” and congratulated herself. The happiness of the evil-minded is black. – Victor Hugo

|

I have known many, many Madame Victurniens in my life, and what Hugo wrote in his novel is true. There are people who take delight in punishing others — who “spend more money, waste more time, take more trouble, than would be required for ten good actions.” The reach and effect of today’s Victurniens has only grown. We are a culture steeped in gossip magazines and cults of bad personality. Many Victurniens become famous for little more than their ability to create miserable drama with an air of confidence — Donald Trump and Rush Limbaugh are leading examples — while everyday others find nearly unlimited opportunities to spread malevolence on the internet.

But what of today’s Fantines? While it may be comforting to think that no such women exist, they do. Accidental pregnancies still happen, fathers still leave, and women the world over — even in progressive countries — still live in poverty, surrender children they can’t afford to raise, or sell their bodies and worldly possessions in order to pay rent and child care. They may be fired from their low-wage jobs for any number of reasons, including spotty daycare or a lack of reliable transportation. And much like Fantine, they may feel like they’re getting somewhere — they may buy furniture on credit and revel in the idea of a better tomorrow — only to have the short legs of hope broken before the race ends.

The Fantine of the 19th century, viewed through a cinematic and historically distant lens, stokes emotions of compassion and justice. Yet, how do we treat women in poverty and single mothers today? As recently as the last political season, the Fantines were dragged into the town square for a hostile public shaming. There are no excuses, they were told. You’re not trying hard enough. You’re a blight on society. Your children aren’t our problem. Get a job, get a better job, get a second job — and who do you think you are, buying furniture (or a tire, or a phone, or a birthday cake) when you’re poor? If you suffer, do it quietly and do it alone. Stay hidden, stay silent, or face our wrath.

*

I have often had the thought that all of life is like an interactive play. We are given a part on the day that we are conceived. We are the wanted, the cherished, the Godly duty, or the unfortunate accident. We are to become the heirs, the beloved, the invisible, or the black sheep. Later, through the magic of human theater, we learn that auditions are always open. The script ahead of us is not yet written. Anything is possible, we are told, and there are no limits.

We spend much of our youth learning our roles and trying on new ones. Over time, we process deeper and broader human plots, and have our characters tested, forged, and occasionally reborn. We memorize lines and lessons that hold meaning for us, and they are not all that different from those of thousands of years ago. What has always been beautiful is still beautiful, and what has always been ugly remains unfinished — perpetual lessons held out for the learning, but never quite absorbed, at least not fully. One ended horror — like the Holocaust — does not stop all similar horrors, although logically, in a world that was quicker and more willing to learn, it would. We ended slavery, at least on paper, but still buy diamonds and shirts made possible by child labor. And so it goes for nearly every injustice under the sun and the comfort is always the same: The stale but hopeful, “At least we’re making progress.”

Eventually, we find ways of being whether we land on Main, or somewhere on the off-off periphery. We gather our thoughts, our experiences, and our loves around us. We build families, passions, and legacies. We strive, we accomplish, and we struggle. And somewhere, always, there are protagonists — our own Victurniens, Javerts, or Thénardiers — who would like to see us broken, failed, or put back in our “proper place.” Among all the noble causes a person can take up in life, the most fundamental one is self-preservation. You can’t change anything in the world at all if you allow the protagonists to silence you or break your spirit . . . which, like knowing when to fight and when to retreat, is another never-ending lesson.

*

Another lesson: What is the difference between a self-made man and a successful man who has been given a leg up? None, because they are one in the same — they are always one in the same, because no man is, or can be, an island in reality. It is only the phrasing and the ensuing perception that creates the difference. One set of words denotes a hero, while the other calls up weaker visions of someone who has been saved. In the play of life, the painted hero is taken as is, flaws and all, but the saved will cause a miserly audience to question worthiness and deservedness. While there may be those who envy heroes for their strengths, it’s an envy that comes with admiration — unlike the kind of jealousy that’s reserved for those who’ve been given an obvious leg-up. The perceived saving of others, even those who have the least, tends to stoke the kind of animus that fumes, “Why him? Why not me? He doesn’t deserve it [insert reason], but I do [insert belief].”

Sometimes, the animus is understandable. We do live in an often nonsensical world where people are more likely to know the name Snooki than Hawking, but notoriety and fame is not the culture most of us live in day-by-day. The famous, whether of the noble or jester variety, don’t dictate our ethics, psyches, or our treatment of each other — they can only ever reflect a certain set of popular values.

But can fictions fuel centuries of delusions? I believe they can and do. The self-made man, the island, the rock — rugged, dependent on no one, and totally self-sustaining — is one such delusion. We live in an interdependent world, where our actions affect more than just ourselves. Which brings me back to Fantine, whose course in life was not solely her own doing (which is a terribly unpopular, but nonetheless true, thing to say in this age of everyone for themselves, by themselves). Fantines, in both reality and fiction, would not be possible without the life-altering actions of scoundrels. The parents who abandon, the lover who runs off, the extorters, the gossips, the bullies, the jailer, the unforgiving society. . .

What would it have taken for someone like Fantine — toothless, penniless, and without family — to rise above her circumstances? Could she have ever done it alone, or would she have needed a hero? If she needed a hero, would she herself be considered unworthy? Was death the only avenue of redemption open to her; the only way to pay for her sins in full? Is this why we cry for Fantine; because she is dead? Are we relieved that such trauma is no longer in our view? What would we have made of Fantine had she lived, and not been rescued by Valjean, or been given a death sentence by Hugo?

What Dickensian twist in the plot would cause a Madame Victurnien to reexamine her punitive heart? What kind of epiphany would it take for a Thénardier to check his greed?

The tragedy, I think, is not that we don’t know, but that we know very well. We have known for as long as the human play has been running — the stark differences between tragic/hopeful, true/false, help/hindrance — and yet we change so very little. We could promote reason, intelligence, potential, and compassion. We could positively alter the course, even by a few degrees, for every person living with poverty, abuse, oppression, or illness. We could, theoretically, toss out familiar scripts and invent new ones — but we can’t even come to an actionable consensus on something as basic as good and evil. I don’t think it’s because we don’t know, but because too many of us are comfortable, and comfort causes complacency as well as obstinance. (I’m reminded of too many memories in the 70s, when no one wanted to get up to manually change the channel, so they would just watch whatever was on, no matter how awful it was.) There are many people who want a new script — who can envision a world radically changed for the better, and who are willing to work and sacrifice for it — but just as throughout history, there are not enough.

I think it may take a shower of red-hot meteors or some other life-changing global event to shake us from our roots.

In the meantime, I’m reminded to stand up for the Fantines in my midst. To lend a hand to those who need it; to see the Victurniens for the vicious gossips they are; and to boycott any business run by a criminally greedy Thénardier.

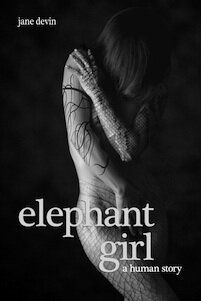

Paperback and Kindle Editions Available Now on Amazon.

Paperback and Kindle Editions Available Now on Amazon.

Add to Google

Add to Google My Yahoo

My Yahoo Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook